Evacuees help firefighters by delivering water pumps from Winnipeg

A northern Manitoba wildfire evacuee who was offered a place to stay in Gimli a few weeks ago did not sit around waiting for the all-clear, but jumped straight in to action to help her community and the firefighters protecting it by purchasing water pumps.

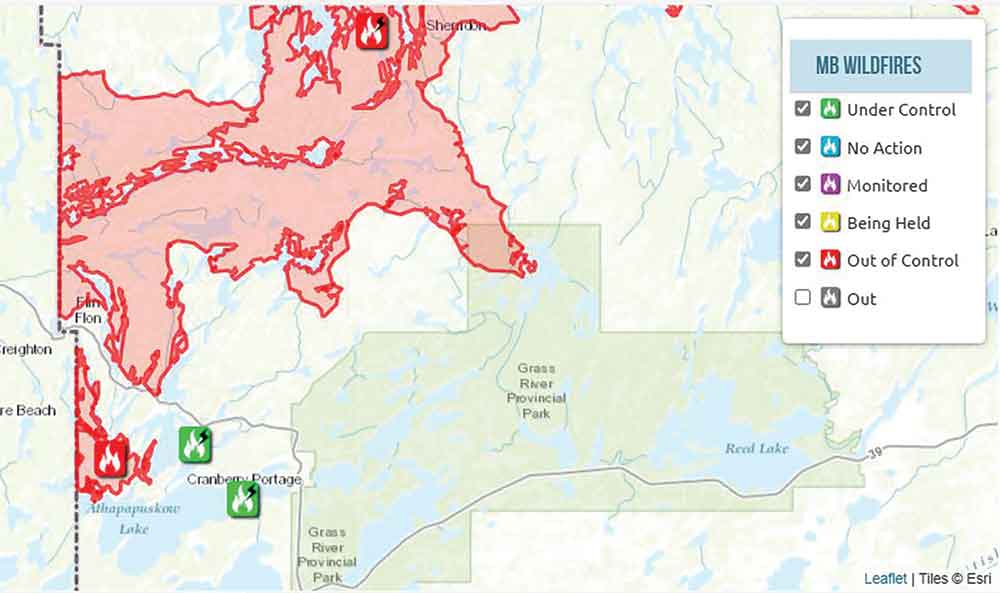

Fires near Cranberry Portage, southeast of Flin Flon, caused the evacuation of residents on May 31. Residents were allowed to return home last Saturday. The Flin Flon-Sherridon fire is still burning out of control as of June 15

Barb Bragg, her daughter, sister and their cats were evacuated from Cranberry Portage at the end of May as huge fires in the Flin Flon region continued to rage and threaten more communities.

Before they were told to evacuate, Bragg said she had posted an update about the fires on her Facebook page a few days ahead of the mandatory evacuation, and Loni Beach resident Salin Guttormsson said if the evacuation order came down, Bragg could stay at her cottage in Loni Beach, a subdivision at the north end of Gimli.

“We had spent a lot of time on northern roads,” said Bragg with reference to a few years back when she and Guttormsson travelled together between northern communities on provincial election-related work. “And she’s a friend on Facebook. When I first posted about the fires to update friends about what was going on, Salin immediately responded back and said if you need a place if you get evacuated, take my cabin. And we did.”

Cranberry Portage is about 46 kilometres southeast of Flin Flon. The massive wildfire in the Flin Flon and Sherridon region was still out of control as of June 15, burning almost 371,000 hectares. Cranberry Portage evacuees were able to return home last Saturday.

Having been evacuated last year because of wildfires around Cranberry Portage, Bragg said residents started feeling a little nervous about the smoke last month as they remembered the flames having moved 20 kilometres in the space of two hours last year. They started paying close attention to the progression of the fires north of them and across the border in Saskatchewan.

“We could see the fire was starting to build. Saskatchewan is not very far away – it’s at the end of lake near us. The fire that affected Denare Beach [in Sask.] started coming down towards the end of the lake. If the winds were strong and the direction right, that fire could conceivably come down the side of the lake and right into Cranberry Portage,” said Bragg. “And the fire circling Flin Flon grew arms on both sides that could reach out to Cranberry given the right conditions. On May 31 we were evacuated.”

After she and her family arrived in Gimli, they took a day or so to get their bearings. Bragg, who’s 70 years old, then swung into action, feeling she had to do something for her community instead of just watching and waiting.

“As I was driving down [to Gimli], I was keeping my eye on a chat where people were asking if everybody was OK, and where are you and so forth. Then the chat took a turn: Denare Beach has been overcome and the firefighters had to leave. It looks like my home is gone. We know so-and-so’s home is gone, they were saying. This was like watching devastation in real time. People on this chat were just finding out their home of 50 years was gone,” said Bragg. “And here I am escaping to a beautiful cabin in Gimli. So, I was racking my brains as to what I could do. I know there are only 25 or 30 firefighters staying behind in Cranberry, and some friends of mine stayed behind to do the cooking for them. I could be doing something.”

Accustomed to driving long distances in the north, Bragg drove to Winnipeg a number of times to purchase water pumps and sprinklers for the firefighters to set up near homes and cottages that sit along the lake in Cranberry Portage.

She then headed north, sleeping in her vehicle along the way, to deliver the pumps to firefighting crews and checkpoints as far north as people were allowed to drive given highway closures and the movement of fire and smoke. She was able to get the pumps sent up to the crews fighting the fires near Cranberry.

She used her own funds to purchase the equipment and also got pumps on behalf of others when they found out she could literally deliver.

“There was a rush to get this equipment. We heard that pumps were becoming a hot entity in the north because we had about 20,000 people evacuated and they need their homes protected,” said Bragg. “One of the fire guys from Cranberry had made an arrangement with Princess Auto [in Winnipeg] to get pumps. Princess Auto offered them a discount. I was able to fit six of them in my vehicle at one time.”

Bragg said she then drove around Winnipeg trying to find sprinklers, but they seemed to be out of stock everywhere. Her sister contacted family members south of Winnipeg, asking them it they could round up some sprinklers. They jumped in their car and drove around to various southern communities before they found some in Altona.

In the end, Bragg made three trips up the highway, delivering 14 pumps and other equipment.

Cranberry firefighters were able to set up some pumps at the lake and run hoses to sprinklers set up on the rooftops of homes and cottages should the fire make a run for Cranberry Portage.

Not only did Bragg’s efforts to get pumps and sprinklers to her community underscore a need for more wildfire resources for northern volunteer fire departments such as Cranberry, whose crew was “jerry-rigging everything they had and trying to find out who had what in their garages,” but it also served as a reminder to residents that they could perhaps play a more proactive role in enhancing their own resilience to wildfires as the climate crisis barrels along.

“[Having equipment to wet down houses] should be the responsibility of the homeowners. It’s not the fire department’s responsibility to have lots of this equipment on hand. Cranberry is a small town of 600 people, and we can’t expect our fire department to have an arsenal of firefighting equipment equivalent to Flin Flon’s or Winnipeg’s. Small departments don’t have the money to do this,” said Bragg. “It really falls on property owners to have this equipment in place so that firefighting crews can come around and turn on the pumps.”

She’s in the process of putting together a contact list of people for a newsletter they’ve established for their subdivision and will be sharing some helpful tips on what people can do to be prepared for the next wildfire emergency and how they can assist their fire department, she said. With the Flin Flin-Sherridon fire still out of control, there could be future evacuations. Having a community inventory of useful fire-suppression tools such as pumps, hoses, sprinklers and shovels can help local crews prevent or mitigate the spread of fires.

In the meantime, the Flin Flon-based Northern Neighbours Foundation, on whose board Bragg sits, allocated $200,000 to five communities in the region – split between Cranberry Portage, Creighton, Denare Beach, Flin Flon and Snow Lake – so that they can purchase additional firefighting resources.

The board had already reviewed applicant proposals before the fires started, but decided to re-allocate the $200,000 to fire resources after the wildfires took off. The foundation’s board had reached out to the five fire departments to ask what they needed, and they came back with a wish list totalling $400,000.

“I was proud of our foundation for pulling that $200,000 back and redirecting it to fire resources,” said Bragg.

She can’t thank Princess Auto enough for giving her community a discount on the water pumps, as well as a “wonderful” auto service business on Osbourne Street that fixed a problem on her vehicle late on a Saturday night so that she could drive north to deliver more pumps, and the Hudson Bay Railway, which put some of the water pumps on a car and shipped them north.

She also extends her gratitude to Salin, whom she refers to as her “evacuhost” (a composite word Bragg made up), for opening her heart and her cottage to her and her family when they had to evacuate.

Guttormson said Bragg had been an “incredible tour guide” during the period she spent up north on election work and they kept in touch afterwards. When the wildfires started, it was a “no-brainer” to offer Bragg and her family shelter.

“The cottage was nowhere close to being in a state where I’d normally have guests,” said Guttormsson, who had to quickly sweep away the cobwebs from patio furniture, buy toilet paper and get the Internet connected. “But I think it was such a relief to Barb. And she knew she could stay here as long as she needed to. I kept repeating that to them. … I had to convince her she wasn’t taking my cottage away from me. It really was a no-brainer. Here, I have this place. …. People taking vacations now are being asked to give up their hotel rooms for evacuees because there is no hotel space and over 20,000 people have been evacuated.”

In addition to ensuring Bragg and her family had a comfortable place to stay (Bragg’s sister eventually stayed with someone in Dunnottar as the family cats don’t get on very well), Guttormsson said she just can’t imagine what it’s like for evacuees to flee their home during a wildfire and wonder if they’ll ever see it again.

“When you know someone who’s going through this – and you’re not just reading about it – it really brings it home as to what they’re going through. It’s mind-boggling,” said Guttormsson. “This has heightened my awareness of how devastating wildfires can be.”

Should Bragg and her family need to evacuate again, Guttormsson said they’re welcome to stay at her cottage.

“There’s more than one benefit to helping someone out: I didn’t feel so useless. You feel like you’re doing something to help others in trouble,” said Guttormsson.