Province expanding paramedic training seats, training more emergency medical responders (EMRs)

The Manitoba Association of Health Care Professionals (MAHCP) says rural regions are still struggling to hire and retain primary care paramedics despite the provincial government’s work on improving emergency services that includes recent announcements to expand paramedic training seats in Winnipeg and the north and train emergency medical responders (EMRs) in rural areas.

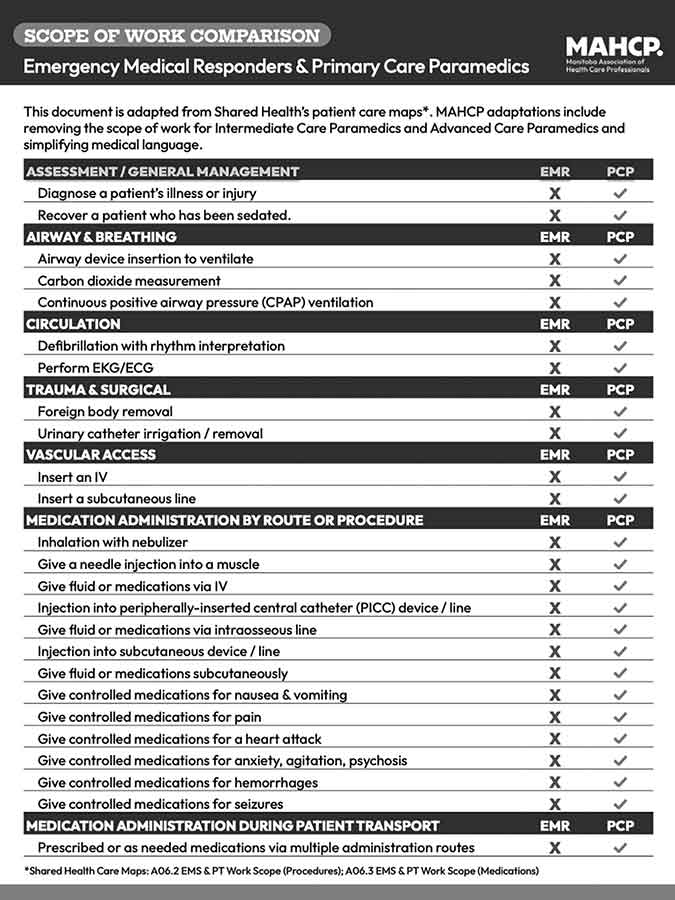

In response to the province’s plan to train emergency medical responders (EMRs) for rural areas, the Manitoba Association of Health Care Professionals put together a scope of work practice chart showing EMRs being unable to perform at the level of paramedics

The government announced Nov. 19 it’s expanding paramedic training seats to strengthen emergency medical services across the province.

Manitoba premier Wab Kinew and health minister Uzoma Asagwara said a new, direct-entry Primary Care Paramedics (PCP) program at Red River College Polytech will add another 14 seats, increasing total primary care paramedic seats to 40. And to further support northern and rural communities, the government added 16 more seats for a total of 32 seats at the University College of the North.

“Our government is opening doors for more Manitobans to pursue careers in emergency care,” said Asagwara in the Nov. 19 news release. “This will help stabilize emergency medical services staffing, reduce wait times and ensure our paramedic workforce reflects the communities they serve. We’re committed to supporting workers from their first day of training through to advanced practice.”

Paramedic losses (rural) have out-paced paramedic gains, according to data analyzed by MAHCP, a union which represents allied health professionals, including rural paramedics.

MAHCP president Jason Linklater gave the government credit for acknowledging the paramedic shortfall, but said the magnitude of the crisis requires a “proportionate” response.

“Today’s announcement about direct-entry paramedic training at RRC Polytech does not represent a significant solution to the paramedic staffing crisis. The magnitude of the crisis requires a proportionate response, and we’re not seeing it. It’s good that the Red River training seats are now full, after years of being underfilled. But those new students won’t be ready to work for years, and meanwhile rural Manitoba continues to lose full-time paramedics due to years of short-staffing, mandatory overtime, difficult working conditions and lack of opportunity,” said Linklater in a Nov. 19 news release.

In terms of paramedic gain up to November 2025, Linklater said Shared Health had a net gain of only one paramedic as the authority is “losing them as fast as they can hire them.”

Over a two-year period, rural regions/EMS zones saw 70 paramedics resign, retire or be terminated, according to MAHCP’s analysis, said spokesperson Karen Viveiros on behalf of MAHCP.

“By our count, and based on monthly turnover reports from the employer, 70 paramedics resigned, retired, or were otherwise terminated from full-time or part-time positions between October 2023 and October 2025 in all rural regions/EMS zones, excluding Winnipeg and Brandon,” she said.

As far as data for the Interlake region in particular, MAHCP doesn’t have a breakdown of how many paramedics resigned, retired or were terminated. But Viveiros said the union can say “with confidence” that all rural regions have experienced “significant turnover and difficulty retaining paramedics due to difficult working conditions and lack of opportunity to move to positions in other locations.”

During the 2023 provincial election campaign, the NDP promised to hire 200 paramedics and re-open three Winnipeg emergency rooms (Seven Oaks, Concordia and Victoria hospitals) in Winnipeg that had been closed by the previous PC government, as well as rebuild the Eriksdale ER. Plans for Victoria and Eriksdale are already underway.

The paramedic vacancy rate in the Interlake is roughly 25 per cent, with 40 vacant, unfilled positions – a number that does not include other positions that are vacant due to paramedics being off related to physical or psychological injuries.

“The 40 positions have remained vacant for well over a year because Shared Health does not want to post positions, which would give paramedics an opportunity to leave the west or the north to come to the Interlake,” said Viveiros. “Despite having approximately 200 vacancies across the province, (mostly permanent positions), Shared Health is only hiring for a handful of specific stations in Prairie Mountain Health and the North.”

Linklater said the union remains willing to work with the government to meet its commitment to hire 200 net new paramedics in its first term.

A shortage of rural paramedics and the ongoing temporary closures of emergency rooms at hospitals in the Interlake-Eastern Regional Health Authority have led at times to delayed response time and lengthy journeys on the highway to get to an open ER. Issues with the 911 telephone service resulted in dropped calls in municipalities such as Fisher and Bifrost-Riverton, and may have contributed to the death of an RM of Fisher man whose family could not dial out to 911.

On the heels of its announcement to expand paramedic training seats, the provincial government said it will help municipalities recruit emergency medical responders (EMRs) by offering a new bursary program and in-community training programs. The training will “support” rural emergency response services.

“This initiative will help local municipalities recruit emergency medical responders and it will start to reverse the damage done by the previous government which dissuaded people from pursuing a career in emergency medicine, especially in rural communities,” said Minister Asagwara in a Nov. 26 news release. “We’re offering financial help to make enrolling in a course more appealing and we’re putting trainees in rural municipalities, where they can get hands on experience on real-world emergency calls and fall in love with rural Manitoba.”

The province said it partnered with the Criti Care Paramedic Academy (in Winnipeg) to offer the emergency medical responder training and provide a new $5,000 bursary for students who complete the training. Graduates who receive the bursary will enter a one-year return-of-service-agreement once hired. This year, students will train in Arborg.

It’s expected that 50-60 EMRs will graduate by fall 2026, complete the Canadian Organization of Paramedic Regulators exam and be eligible for hiring into provincial EMS, states the news release.

Criti Care’s website has an application form for its EMR program, but the Record could not determine what its training entails.

After seeing the province’s EMR announcement, MAHCP put together and published a “scope of work comparison” between EMRs and paramedics. Adapted from Shared Health’s patient care maps – which describes medical care and interventions – MAHCP determined that EMRs cannot perform duties paramedics are trained to do.

For instance, EMRs cannot diagnose a patient’s illness or injury, insert an airway device to ventilate a patient, perform defibrillation with rhythm interpretation, perform EKG/ECG, remove foreign bodies from a patient, perform urinary catheter irrigation/removal, insert an IV, insert a subcutaneous line, give fluid or medications via IV, give an injection into a muscle, give controlled medications for a heart attack, hemorrhages, seizures, anxiety, psychosis, pain, nausea and vomiting, and give medications during patient transport.

MAHCP said in a Nov. 27 post that it is not “advocating against” EMRs, but that an alternative level of care will not solve the paramedic staffing crisis.

“This week, the province announced financial support for students and in-community training programs to recruit Emergency Medical Responders (EMRs) in rural Manitoba. While the announcement was framed as a way to increase ambulance coverage and shorten wait times, MAHCP is concerned about the level of care EMRs can provide in a critical emergency, which … Minister Asagwara called an ‘alternative level of care,’” states MAHCP. “Manitobans aren’t looking for an alternative; they want the 200 paramedics the NDP government promised, only 18 of which have been added since October 2023.”

MAHCP’s president Jason Linklater added that EMRs are “valuable professionals” who play an important role in supporting emergency medical services (EMS), particularly in stable patient transport and medical first response. But EMRs’ limited scope of practice and clinical training “does not allow them to provide anywhere near the same level of care that paramedics can.” And putting EMRs rather than paramedics on ambulances puts them and patients at risk. Two fully trained paramedics are required to deal with high-acuity, time-sensitive calls such as cardiac arrests, severe trauma, violent or unstable patients, obstetrical crises and complex medical emergencies.

“Shared Health and our provincial leaders are opting for fast and cheap — a long-term solution that isn’t good for rural Manitobans, or any Manitoban, when what you need is a highly skilled primary care paramedic (PCP) to treat and stabilize a patient,” said Linklater.”

Among the measures to improve rural emergency services, MAHCP said the government/Shared Health needs to ensure the continuous hiring of paramedics by posting and filling all vacancies promptly, make paramedic training more accessible to rural Manitobans, cover tuition for paramedic training including EMR-path students, require new EMRs to complete paramedic training with a set time period, and offer incentives and cover the costs of travel and accommodation in hard-to-fill areas.

The Record asked Shared Health how many paramedics were hired for the rural region (up to November 2025), how many paramedics left the rural region (up to November 2025), a description of EMR training, when the EMR program starts in Arborg and how many students have enrolled.

Shared Health responded, saying it will look into the questions but did not provide answers by deadline.