Linguistic researchers from two universities in Germany have been studying the way people of Icelandic descent in the Gimli, Riverton and Arborg areas speak to determine the extent to which English and Icelandic influence each other.

Co-principal investigators Christiane Ulbrich from the University of Cologne and Nicole Dehe from the University of Konstanz, along with their PhD student Meike Rommel from the University of Konstanz, spent a few weeks in the area where they had 29 participants from Gimli, Riverton and Arborg take part in a number of sessions that took about six hours to complete.

Research on heritage languages, defined as the language of one’s ancestry or as a minority language learned by children at home, provides insight into how languages can influence each other and whether a heritage language can eventually become moribund (endangered).

Dehe said she and her colleagues were delighted to get so many participants, and that they were willing to “spend so much time with us.” They’re interested in the Icelandic spoken in this region of Manitoba and will be comparing it to modern Icelandic currently spoken in Iceland. They chose to study Icelandic speakers here – as opposed to places such as North Dakota or Minnesota – because of the history of New Iceland in Manitoba.

“Right now we’re interested in one particular group of speakers, those who we call the moribund speakers, those who grew up with Icelandic until school age and either continued [speaking it] or didn’t but then had English became dominant,” said Dehe. “We are interested in the comparison between the varieties, the influence that English has on the Icelandic spoken here and the other way around, the influence of Icelandic on English in the speech of the speakers who have both languages. And in the long run, there will be implications for the way certain speech phenomena are stored in the brain and learned or acquired by children.”

The study will also look at “learner Icelandic,” or language that was not acquired when the speakers were children but was learned as a second language later in life, say in university.

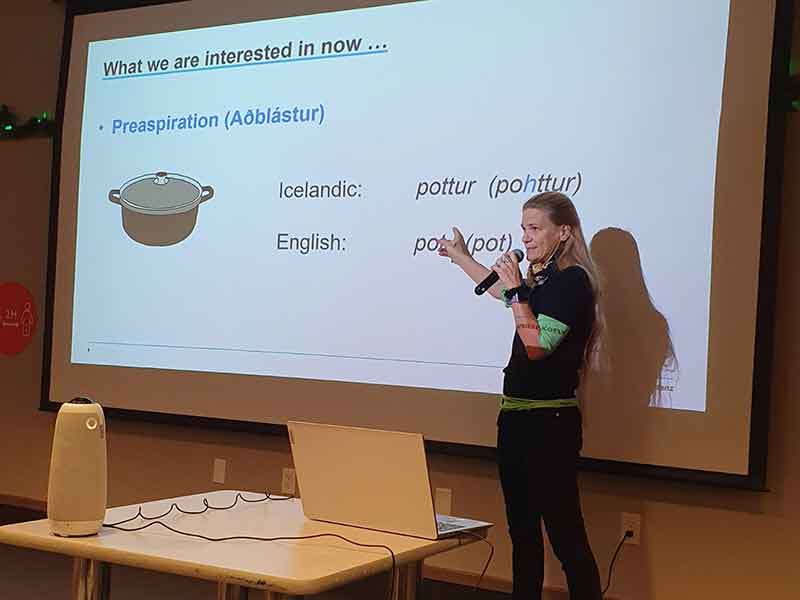

Dehe said they are focusing on two particular linguistic phenomena: word stress and pre-aspiration (a phonetic feature that uses the expulsion of air) to see whether heritage Icelandic speakers who’ve grown up in a dominant English-speaking environment maintain characteristic elements of their ancestral language.

In word stress, English and Icelandic speakers typically put a different emphasis on the same word. For example, the stress on the word “professor” when spoken by Icelandic speakers falls on the first syllable in which the “pro” is emphasized. The word “America” spoken by Icelandic speakers would typically have the stress also fall on the first syllable in which the “ahh” is emphasized.

“We are interested in the way one language influences the other,” said Dehe “We want to know whether Icelandic speakers [keep] their stress on words that are stressed differently in English. Maybe the Icelandic speakers here don’t say ‘Ahh-merica’ anymore, but they say ‘America’ when they’re speaking Icelandic. It can happen the other way around, too.”

The other phenomenon they’re interested in is pre-aspiration in which there is an expulsion of air when pronouncing certain words. For example, Icelandic speakers may pronounce the word pot (kitchen utensil) as “pot-ahh.”

The way one language influences another will tell the researchers about how languages are acquired and how they are stored in the brain, said Dehe.

NIHM executive director Julianna Roberts said the researchers contacted the museum for assistance in finding volunteers to interview. Gimli resident Elva Simundsson also helped get things set up for the organizers. She and Roberts created a list of Icelandic speakers and Simundsson phoned them to organize the first round of interviewees.

The museum also provided the researchers with space to conduct their interviews

“This is the fifth time that linguists from around the world have come to study the Icelandic that is spoken here as it is a heritage language and is unchanged since the Icelanders came over in 1875,” said Roberts. “These researchers plan to come back in March as they were so pleased to have found such a great amount of speakers to study.”

Gimli resident Shirley MacFarlane, who grew up in Riverton, was a participant in the study and said she found it very interesting to learn (afterwards) about the purpose of the study and the influence of English on Icelandic, which was her first language at home.

“We lived on the homestead with my grandfather who had come here [from Iceland] in 1886. He knew some English before he moved here, but I don’t remember him speaking English,” said MacFarlane. “My father and aunt also spoke Icelandic and we were expected to answer them in Icelandic. I didn’t know much English before I started school in Riverton.”

One of the exercises entailed naming objects such as coat hangers and clothes pins.

“They had me looking through a picture book with two pictures on a page and I had to tell them in Icelandic what the objects were,” she said. “In another session we had to do the same thing but answer in English. And they were recording our voices in all the answers to the pictures and studying our voices.”

MacFarlane said after the exercises wrapped up, the researchers explained what they were studying and pointed out some differences such as rising inflections [or upspeak] on some words.

“[The researchers] said they’re finding that English is sort of creeping into the Icelandic language, which really makes sense in the case of my grandparents and a lot of other people who immigrated here,” she said.

There are slight accent differences among Icelandic speakers from Arborg, Riverton and Gimli, and that some people can pinpoint where someone grew up, said MacFarlane. She has been told by other Icelandic speakers that they can tell she grew up in Riverton because of her “Riverton accent.” She asked the researchers whether they could detect accent variations; they said they didn’t hear those differences.

MacFarlane said she takes part in social gatherings on Wednesdays at the New Iceland Heritage Museum where people converse in Icelandic in order to “keep the language alive.”

“A lot of times English will creep into our speaking because you might be attempting to say what you did last week but then you run into words you don’t know in Icelandic and you insert English words in there.”

Gimli resident Ingrid Roed also took part in the study, saying she was exposed to Icelandic as a child and picked up a few words, but didn’t learn to speak it fully until later in life. She qualified for the study because she learned the language in Gimli.

“I have fair bit of Icelandic now and I can carry on a simple conversation, but I don’t consider myself fluent,” said Roed. “But the Icelanders who hear me say I speak quite well.”

In addition to identifying pictures and telling the researchers in both Icelandic and English what they were, Roed said there was a story-telling exercise – based on a series of images – the participants took part in.

“The researchers gave us a little description or summary so that we understood what was going on. Then we were to tell them a story of what was going on. We did it in Icelandic and we did another session in English,” said Roed. “What they were looking for was not so much if we knew Icelandic words and how well we speak either language, but how we pronounce words and whether the Icelandic influences our English pronunciation or the way we say things, or whether English influences our Icelandic pronunciation and our style of speaking.”

Like MacFarlane, Roed said there are subtle differences between Icelandic speakers in Gimli, Riverton and Arborg, and that some people, like her aunt, can tell just by listening what town someone is from.

The study, which is titled “Cross-linguistic influence in phonology: the case of heritage Icelandic,” is being funded by the German Research Foundation for a period of three years, said Dehe. They have a number of publication options, including international linguistic journals, journals focusing on second-language research or journals dedicated to Scandinavian languages.

Based on the large datasets they’ve gathered in Manitoba and in Iceland, Dehe said she expects she and her colleagues will be able to publish more than one paper. PhD candidate Meike Rommel, for instance, intends to complete her thesis based on part of the research.

Dehe said they’re planning to return to Manitoba in February or March to study Icelandic speakers who learned the language much later in life. They’ll be reaching out to the University of Manitoba’s Icelandic department for assistance.

Anyone interested in participating in that leg of the study is encouraged to get in touch with the linguistic researchers at their respective German universities in Koln (Cologne) and Konstanz.